1,950 mile-long open wound

dividing a pueblo, a culture,

running down the length of my body,

staking fence rods in my flesh,

splits me splits me

me raja me raja

Gloria Anzaldúa

Borderlands/

La Frontera:

The New Mestiza

Gloria Anzaldúa

Gloria Anzaldúa: Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 25th Anniversary 4th Edition, Aunt Lute Books, San Francisco, 2012

Part memoir, part history, part poetry, myth and incantation, Anzaldúa’s text is a visionary weaving of multiple genres and languages.

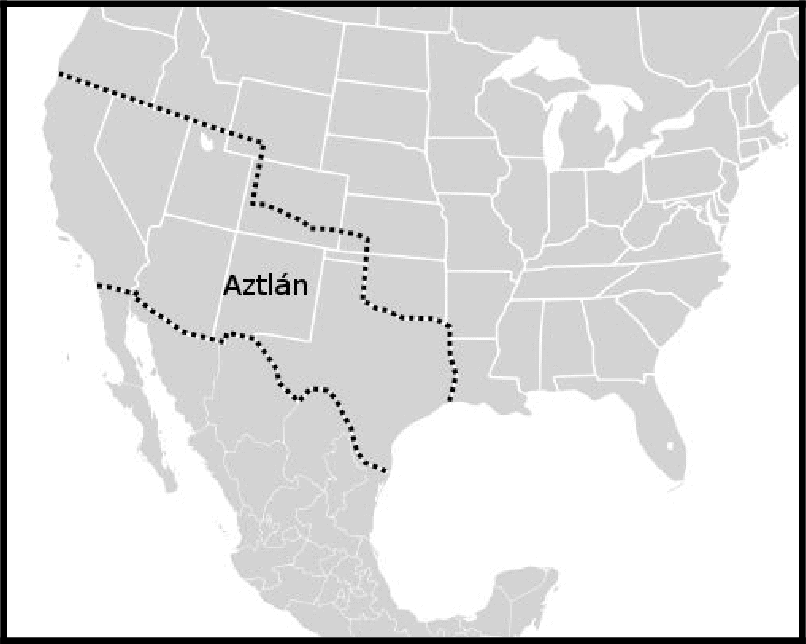

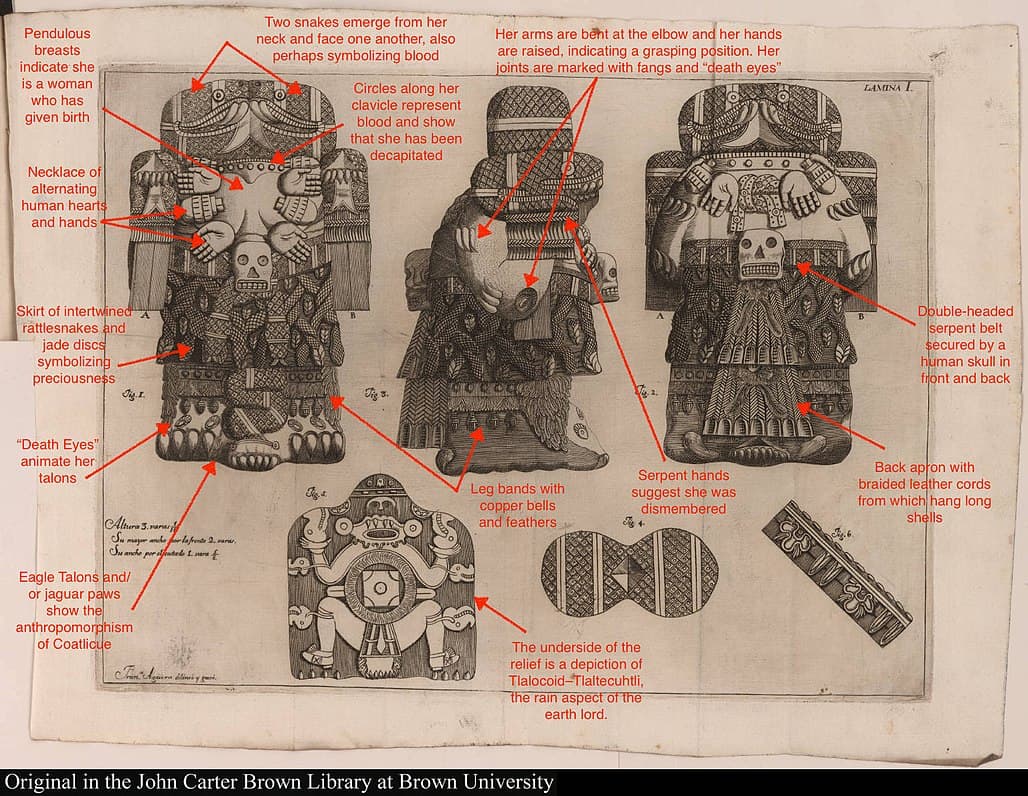

Her first chapter moves from poem to an alternative narrative of U.S. southwest history (Aztlán) that traces the land’s people from the first inhabitants who crossed the Bering Straights in 35000 BC, to the Cochise and Aztec cultures, to 16th century Spanish conquerors, to 19th century U.S. invasion of the land. Her second chapter is an exploration of gender and sexuality within Mexican culture. She lives at the borders of all these cultures, feeling an outsider, until she begins to identify with the Mexican mother goddess Coatlicue, who provides her with the power and imagery of self-creation through an exploration of the Shadow-Beast, whom Coatlicue represents. Feathers, serpents, blood all become symbols for Anzaldúa’s connection to the earth, to her people, and to herself. The final chapters set out Anzaldúa’s text set out her mestiza consciousness, a consciousness that perceives from all the different identities that exist inside Anzaldúa. This is a shifting consciousness that moves swiftly across borders and that denies none of her many perspectives. In Anzaldúa’s description, “She puts history through a sieve, winnows out the lies, looks at the forces that we as a race, as women, have been part of” (104). After confrontation with the cultures she in which she is enmeshed, after the “rupture,” she must “reinterpret[] history…use[] new symbols…shape[] new myths…adopt[] new perspectives toward the darkskinned, women and queers. She strengthens her tolerance (and intolerance) for ambiguity. She is willing to share, to make herself vulnerable to foreign ways of seeing and thinking…Deconstruct, construct” (104).

Why This Text is Transformative?

Anzaldúa’s flow between languages is more than code switching. It is an enactment of mestiza consciousness.

This can be an intimidating text, especially for the non-Spanish speaker. Ask students to observe how they respond to the shift between Spanish and English throughout the text. Anzaldúa’s flow between languages is more than code switching. It is an enactment of mestiza consciousness. The same is true for the flow between genres in the text. Some students will feel empowered by Anzaldúa’s flow between languages and genres. Other students will feel they are missing something by not being able to interpret the Spanish sections. Other students may have a response to Anzaldúa’s counter narrative to U.S. narratives of exceptionalism, heroism, freedom, opportunity, and individualism. All student responses may be a segue into Anzaldúa’s discussion of the Shadow-Beast. Students may be fascinated by Anzaldúa’s discussion of shadow: “Not many jump at the chance to confront the Shadow-Beast in the mirror without flinching at her lidless serpent eyes, her cold clammy moist hand dragging us underground, fangs bared and hissing” (42). It is this confrontation with the shadow that consciousness transfigures: “’Knowing’ is painful because after ‘it’ happens I can’t stay in the same place and be comfortable. I am no longer the same person I was before” (70).

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

Chapters 1-2

Breaking the text into chapters 1-2, 3-4 and 5-7 is a good way to cover the text in three-four class periods. The following questions focus on chapters 1-4.

Chapters 1-2

1) Read the poem that begins chapter 1 (“Wind tugging at my sleeve”). What images stand out for you in this poem? Notice the ways that the speaker in the poem is tied to the land. What about the land holds this speaker? Is there any land that you feel connected to in this way?

2) Chapter 1 includes a counter narrative to U.S. Southwest history. What narrative is Anzaldúa telling here. Choose words and phrases that indicate her perspective on the players inside this narrative. Are any of these words or phrases surprising to you?

3) What significance is there in Anzaldúa’s flow between English and Spanish? What is your response to Anzaldúa’s use of language?

4) What does Anzaldúa achieve by flowing between multiple genres? Does this have the same significance as her shift between languages?

5) What is the significance of the border imagery in Anzaldúa’s text? Do you have any experience coming up against borders in your own life?

Chapters 3-4

1) Anzaldúa says that when her father died, her mother covered the mirrors: “she didn’t want us to ‘accidentally’ follow our father to the other side” (64). What is the significance of the mirror imagery here? In what way is it connected to the shadow rituals Anzaldúa constructs for herself?

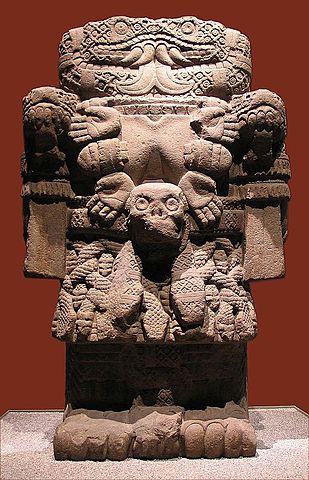

Show an image of Coatlicue:

2) Why is Coatlicue a significant figure in Mexican mythology? What is the significance of Anzaldúa choosing her as the figure to bring her into the shadow-world? Do you have a response to the figure of Coatlicue?

3) Anzaldúa confronts this Shadow-Beast as she moves toward greater knowledge and autonomy of self. What is your understanding of the shadow that Anzaldúa talks about? What is contained within the shadow she confronts and what effect does confronting it have for her? Have you ever confronted a Shadow-Beast in your own self? If so, what happened?

Building Bridges

Consider pairing Anzaldúa’s mestiza consciousness with DuBois’s double consciousness and Audre Lorde’s radical feminist identity

I have also found an interesting comparison between Anzaldúa’s approach to her text with its crossing genres and incantation to Coatlicue to Plato/Socrates’ treatment of the soul.

There are also many similarities between Anzaldúa and Morrison’s novels, including the importance of naming, the life-giving symbol of the snake, the importance of ancestors, history and narrative.

Supplemental Resources

Statue of Coatlicue displayed in National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City

Coatlicue Statue & Myth

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

English/Composition Studies

Humanities

Sociology

Area Studies

Page Contributor