Nor will the beautiful appear to him in the guise of a face or hands or anything else that belongs to the body. It will not appear to him as one idea or one kind of knowledge. It is not anywhere in another thing, as in an animal, or in earth, or in heaven, or in anything else, but itself by itself with itself, it is always one in form; and all the other beautiful things share in that, in such a way that when those others come to be or pass away, this does not become the least bit smaller or greater nor suffer any change.

Plato

Symposium

Plato

Nehamas and Woodruff, ISBN: 978-0872200760

Benardete and Bloom, ISBN: 978-0226042756

The "Symposium" consists of a series of speeches about love given by Socrates and his friends during a drinking party at the house of Agathon.

Having overindulged the night before in celebration of Agathon’s award winning play, the group agrees to pace themselves tonight by means of their speeches to the god of love. Phaedrus starts things off, followed by Pausanias and Euryximachus. Next, Aristophanes delivers his unforgettable origin myth, explaining our unconquerable urge to unite with our one true love as a literal seeking out of our other half. After Agathon delivers a beautiful but sophistical speech praising love, the dialogue culminates with Socrates telling the group about what he learned from Diotima, the woman who trained him in the erotic arts. According to this teaching, love is a desire for the good eternally, and it achieves this through giving birth, both physically and spiritually. He explains how the true initiate into the mysteries of love begins by loving a single individual and ends by experiencing the Form of Beauty itself. Finally, a highly inebriated Alcibiades busts into the party and is angry to find Socrates there. The dialogue ends with Alcibiades giving a speech comparing Socrates to a satyr for his ability to enchant people with philosophy.

Why This Text is Transformative?

Of all the dialogues, the Symposium is the most charming presentation of the classical Platonic thesis—that the good, the beautiful, and the true are one.

Of all the dialogues, the Symposium is the most charming presentation of the classical Platonic thesis—that the good, the beautiful, and the true are one. Each of the speeches in it captures a different facet of the complex nature love: passion, desire, sex, inspiration, affinity, and even anger and frustration. Finally, the mystical ascent up the ladder of love, moving from the commonplace to the revelatory vision of the Forms, is a perfect expression of the essential philosophical movement as conceived by Plato.

A Focused Selection

Study Questions

1) Why does Aristophanes get the hiccups?

2) Think about the claims made about love in each of the speeches before Socrates’ (Phaedrus, Pausanias, Eryximachus, Aristophanes, and Agathon). How do each of them reveal something true about love? Now think about Socrates’ speech. How is Socrates’ speech a speech about love? How is Alcibiades’ encomium to Socrates a final speech about love? Which speech resonates with your experience(s) of love?

3) Socrates claims that love wants to possess the good forever, and therefore must involve immortality. In what sense and how does ascending the “ladder of love” achieve this immortality? Is this satisfying to you?

4) Socrates’ position seems to be that when you are in love with someone, what you are responding to is not the individual per se, but the Form of Beauty as instantiated in the individual. How satisfying is this as an account of the experience of love? If you are not responding to the Form of Beauty as manifested by that individual, what are you responding to?

Building Bridges

A Recommended Pairing

A wonderful short novel by Graham Greene, Monseigneur Quixote, recasts Cervantes’ magnum opus in a way that captures much of the humor and pathos in a more modern context, as the adventures of a Roman Catholic priest and a communist mayor taking to the road together in Spain during the Franco years. The richly imagined characters and their conversations make it clear that the issues that drive Don Quixote’s idealistic quest are not raised only in books of chivalry. How do we live with a commitment to the ideals of a religious faith or a political ideology which, though noble, may not fit easily with and may have unfortunate consequences in the unforgiving world in which we find ourselves? What difference does friendship make in our lives?

Supplemental Resources

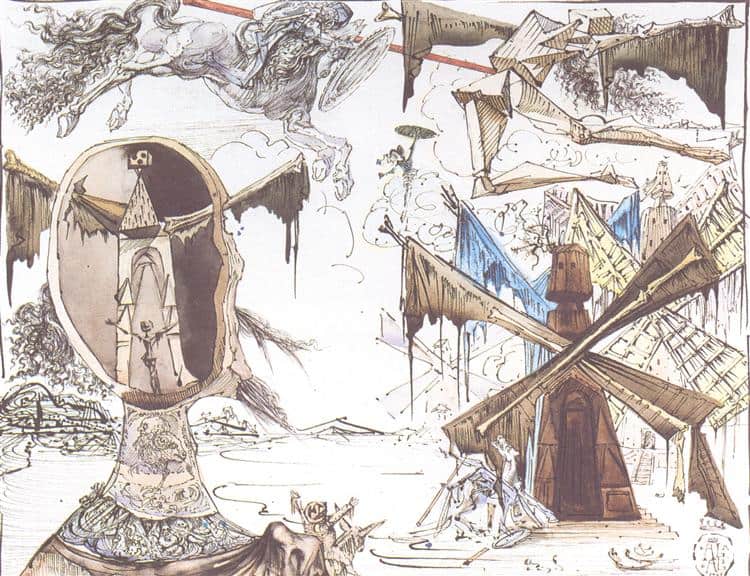

Don Quixote and the Windmills, 1945 - Salvador Dali - WikiArt.org

Don Quixote has been an inspiration for many visual artists. Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali returned to the novel multiple times throughout his long career, creating sketches, paintings, and sculptures of Don Quixote and Sancho, depicting important episodes in the book. A pairing of an episode with one of Dali’s works can lead to a stimulating discussion.

What details do students notice? What do his artistic choices suggest about his interpretation of the characters? To the extent that students are familiar with the story of Don Quixote, it is likely to be as it is filtered through the musical The Man of La Mancha. The musical has its own merits, and is framed by the interesting device of placing Cervantes on stage as a narrator, but of course it is impossible for it to capture much of the complexity of the book – and it alters the ending dramatically. Students may find it interesting to compare the two endings.

Text Mapping

Discipline Mapping

Area Studies

Humanities

Philosophy & Religion

Page Contributor